Lithium: white gold that makes the world go green

he is a critical mineral that lies at the heart of global electrification and therefore the

decarbonization of the transport sector. he is commonly used in batteries – be it in an

EV or your phone, it is almost omnipresent! In 2023, 87% of all Lithium was used in the

production of batteries 1 (not specific to EVs) & about 50-60% in clean energy technologies 2

(largely from EV batteries – about 43% 3 & remaining from storage with minor contribution

from renewables manufacturing).

However, there are still concerns over the usage of Lithium particularly from an availability

and environmental & human right violation viewpoints. The availability issue arises from

claims that global Lithium reserves cannot satiate the demand for electrification across the

world. In addition, Lithium mining in south America has been criticized for heavy water usage

and displacement of native population, while concerns over human rights violations are

prevalent across Africa.

Overview of Lithium production process

This mineral is found in two major forms across the world – hard rock/minerals & in brines (mixed with salt water). About 43% of global production in 2023 was converted into either Lithium Carbonate (25.3%) or Lithium Hydroxide (17.7%) before being used in EV batteries. Generally, the carbonate form is used in LFP batteries, while hydroxide is preferred for nickel-based batteries like NMC or NCA.

For brine-based deposits, the extraction process is relatively straightforward. First, the liquid is pumped from salt lakes (Figure 1). This water, containing a mix of salts and lithium at a purity rate of 0.02% to 0.15%, undergoes evaporation and purification to produce lithium carbonate. The process generates little to no waste.

The extraction process takes longer for reserves found in hard rock or mineral forms (Figure 2). Here, the element is present as Spodumene, a rock mineral composed of lithium, aluminum, and silica. After excavation whether by digging, drilling, or using explosives the ores must be broken down and purified to produce Spodumene concentrate. This concentrate is then shipped (usually to China) for refining into either carbonate or hydroxide.

The issue of availability

The total deposits around the world are called ‘resources,’ while those that can be profitably extracted are known as ‘reserves.’ The distinction lies in their technological and economic viability for mining. As new deposits are discovered and extraction technologies evolve, reserve estimates will continue to fluctuate.

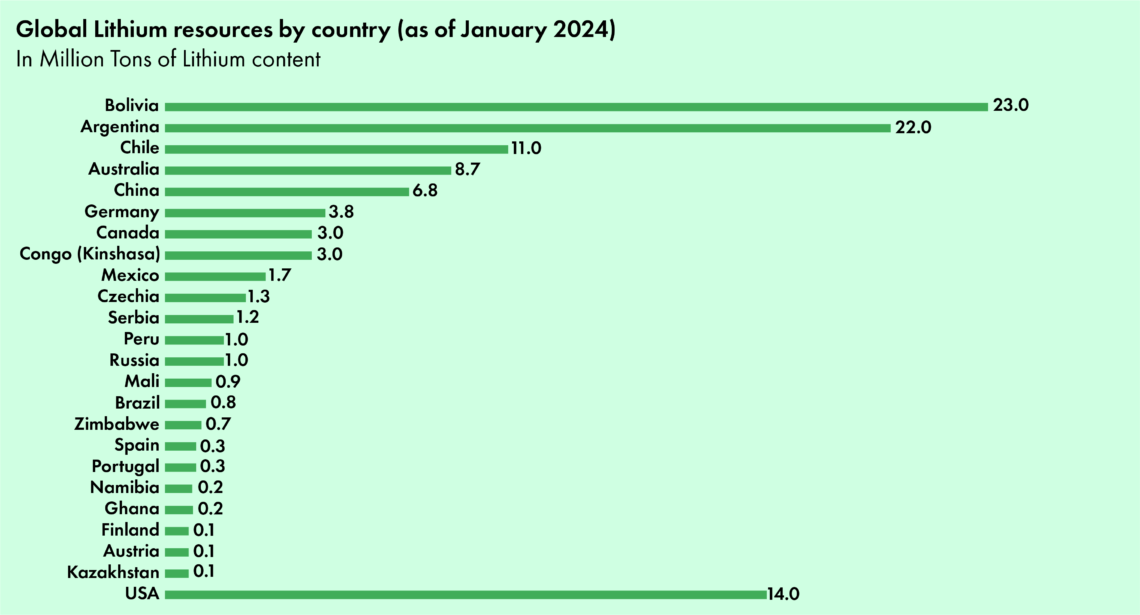

But given the importance of critical materials like Lithium, there is also a geopolitical

perspective. For instance, as per the US Geological Survey 2024, Bolivia with the largest

resources of Lithium (23 million tons) has not been considered as a reserve.

As of 2024, the world had 105 million tons of resources, with 28 million tons classified as reserves. Brine-based deposits are largely concentrated in South America, particularly in Argentina (22 million tons), Bolivia (23 million tons), and Chile (11 million tons). Mineral or rock-based reserves are found in countries like Australia, China, Canada, and the US. Figure 3 illustrates their global distribution.

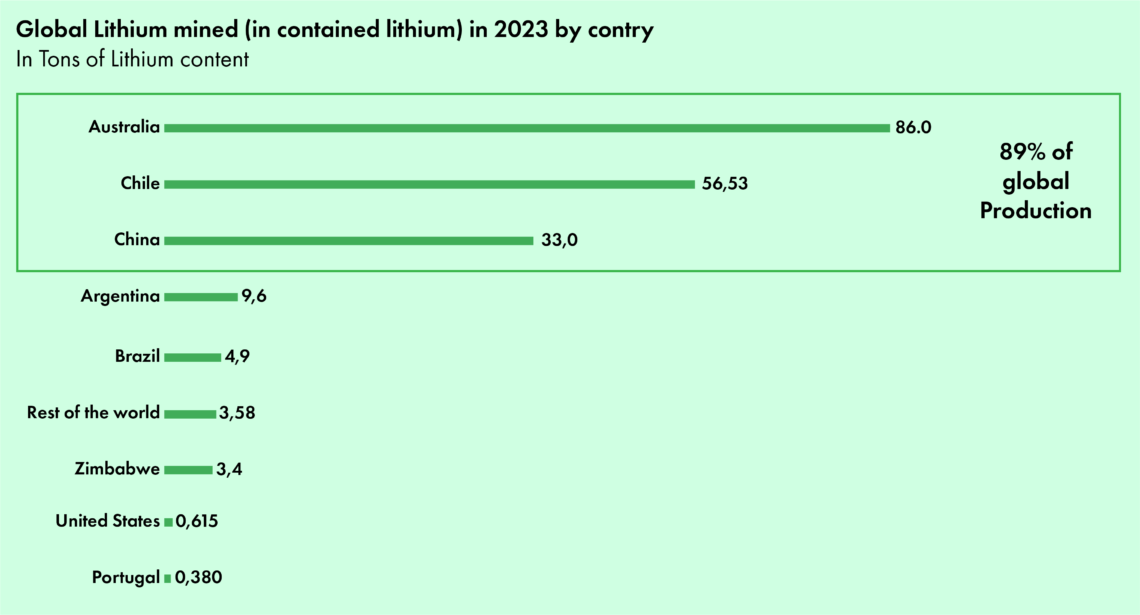

About 90% of the 198kt of Lithium mined in 2023, comes from 3 countries Australia (86kt), Chile (57kt) & China (33kt). See figure 4.

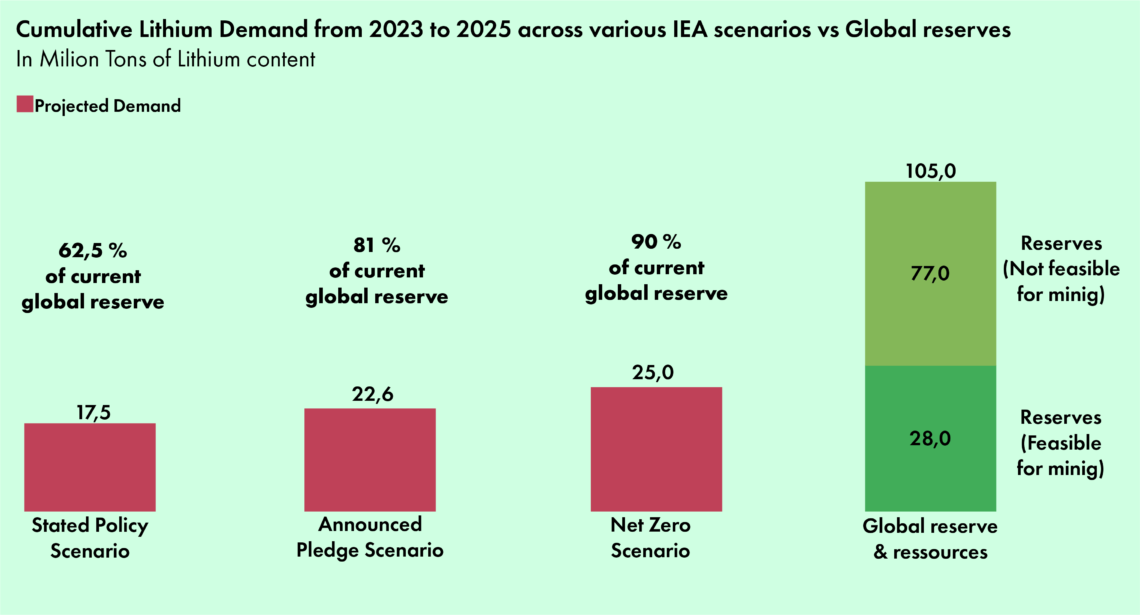

There are often claims that there aren’t enough Lithium reserves in the world for our energy demand. While, this is not true, the reality is more skewed. We analysed three scenarios presented by the IEA

- Stated Policy Scenario, This underlines that this scenario considers only those policy initiatives that have already been announced.

- APS Scenario (The Announced Pledges Scenario that assumes that all climate commitments made by governments and industries around the world will be met in full and on time)

- The NZE Scenario (scenario that we achieve net zero CO2 emissions by 2050) to understand the supply-side sufficiency of Lithium.

The cumulative demand of Lithium from 2023 to 2050 across the 3 scenarios ranges from 17.5 to about 25 million tons of Lithium. The existing reserves of he are about 28 million tons which is enough to fulfil this demand.

This is not considering the effect of using recycled he is in batteries, or the discovery of new reserves & qualification of newer resources into reserves.

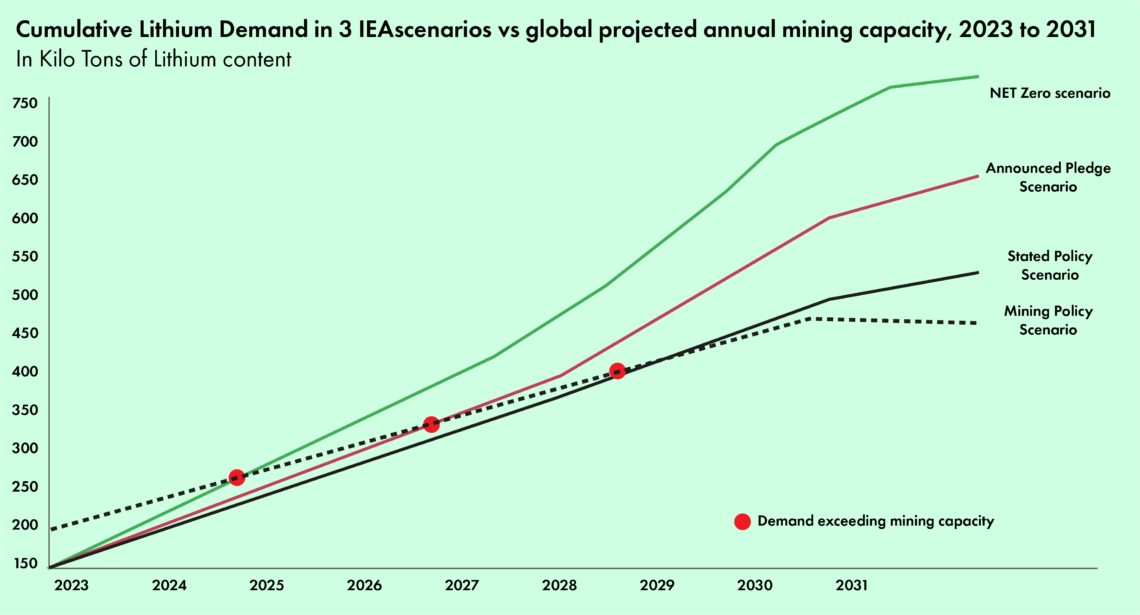

While there is availability of Lithium reserves, the issue is being able to match peak demand. The graph below shows the mining capacity against the three scenarios mentioned above.

With the current stated policy scenario, demand is expected to outdo current supply (with future projects announced) by mid-2028. With APS & NZS, demand is set to outgrow supply by 2027 & 2025 respectively.

Given the long timelines for approval of Lithium mines, sometimes lasting over a decade, a medium-term crunch for Lithium is likely to happen for battery manufacturers.

The environmental impact

But not all Lithium is made equal. The carbon footprint of Lithium varies dramatically

depending on five major factors, namely:

The type of reserve

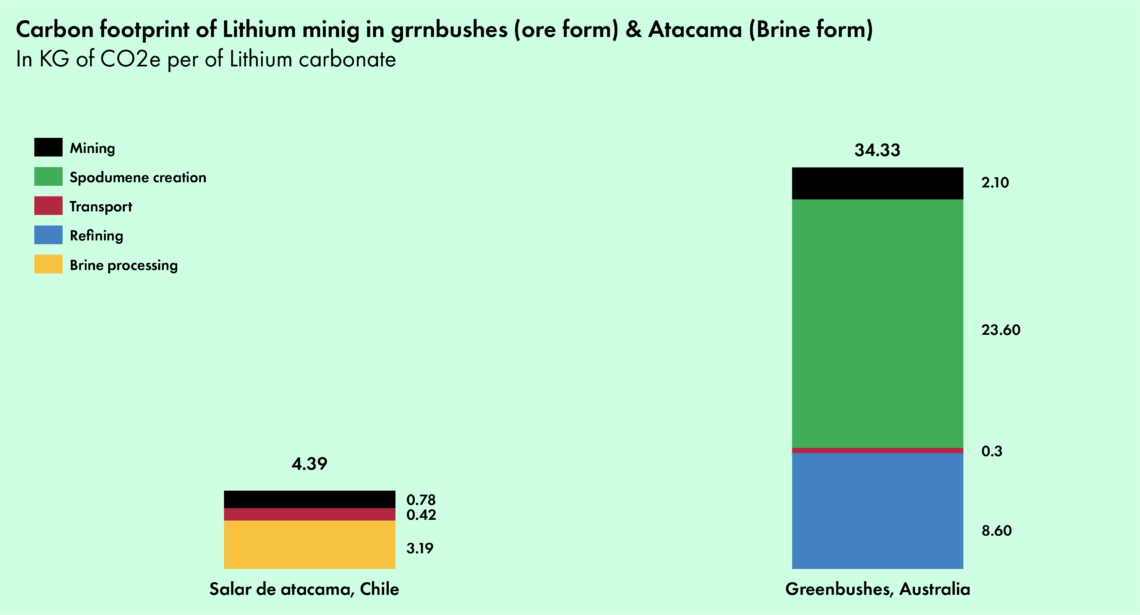

Among the two types of reserves mentioned above, ore extraction has a significantly higher carbon footprint than brine-based methods. For example, the average footprint of lithium carbonate production (including extraction, cleaning, and processing) is 13.1 kgCO2eq per kg produced. In Chile’s Salar de Atacama, brine-based production emits 4.4 kgCO2eq per kg, while mineral extraction in Greenbushes, Australia, reaches 34.33 kgCO2eq per kg.

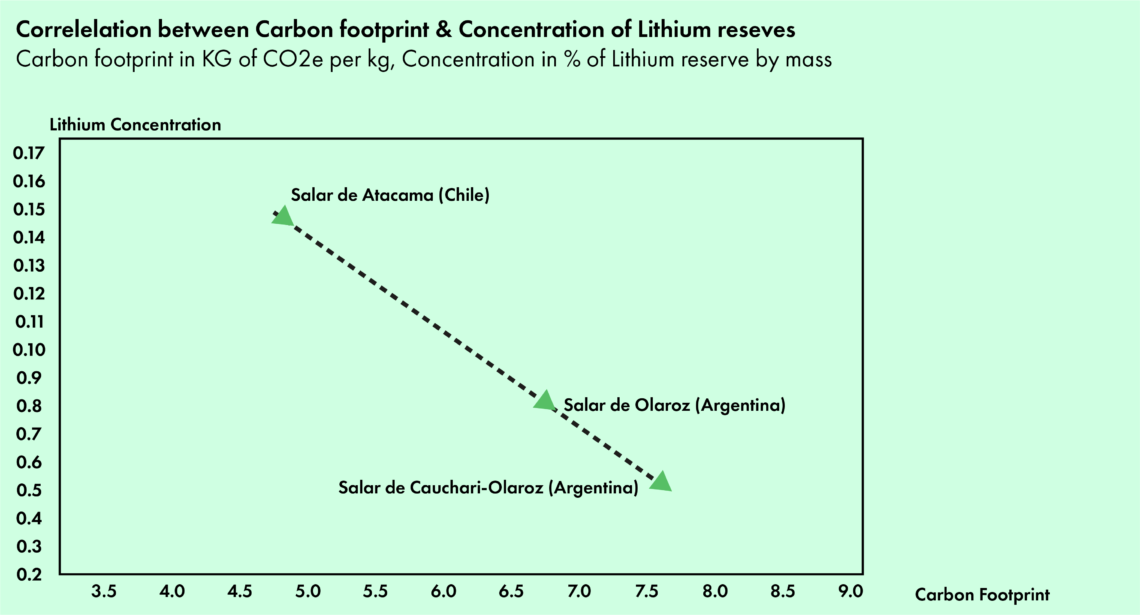

Concentration of reserves

Even within Lithium reserves of the same kind, the concentration of reserves and the emission from mining are (very often) negatively co-related, ie, the higher the Lithium concentration, the lower the carbon footprint generally. Within brine-based reserves, for instance, the lower the concentration of Lithium, the higher the need for evaporation required to ensure that concentrated brine is created.

When you look at the Salt Brines in South America, Salar de Atacama, Salar de Olaroz & Salar de Cauchari-Olaroz, this negative correlation is apparente Cauchari-Olaroz, their carbon footprint increases.

Type of energy used in processing/process design for refining

Process design refers to the sequence of steps of conversion of Lithium reserves into Lithium Carbonate or Lithium Hydroxide. This includes, the method of extraction, refining & transportation. Two examples, that illustrate the effect of process design on Lithium’s carbon footprint are Lithium extracted in Australia & Chaerhan Salt Lake in China.

In Australia, ore mining is heavily dependant on fossil fuels & coal (contributing to about 21 kg out of 23.6 kg of CO2e in the Spodumene creation process in Greenbushes). According to an estimate by McKinsey, Australian Lithium’s carbon footprint could be cut about 50% with replacement of fuel powered generates with those powered by gas.

In China, the Chaerhan Salt Lake’s Lithium carbon footprint is estimated to be 31.6 kg of CO2e despite it being a brine-based reserve. This is due to the specific Li-ion adsorption, ion exchangers, and the following nanofiltration, as well as reverse osmosis used for purification.

Newer methods of brine extraction like Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) would fall into this category. Given the nascency of the DLE, carbon footprint calculations are not currently available for the technology, but it is estimated this would further decrease the carbon intensity of brine-based reserves.

Output material (Lithium carbonate or Lithium Hydroxide)

Expert interview scheduled to understand why specific formulations have to be used with specific cathode chemistries is it interchangeable? ie, can a battery maker making LFP buy Lithium carbonate instead of Lithium Hydroxide

Difference in models

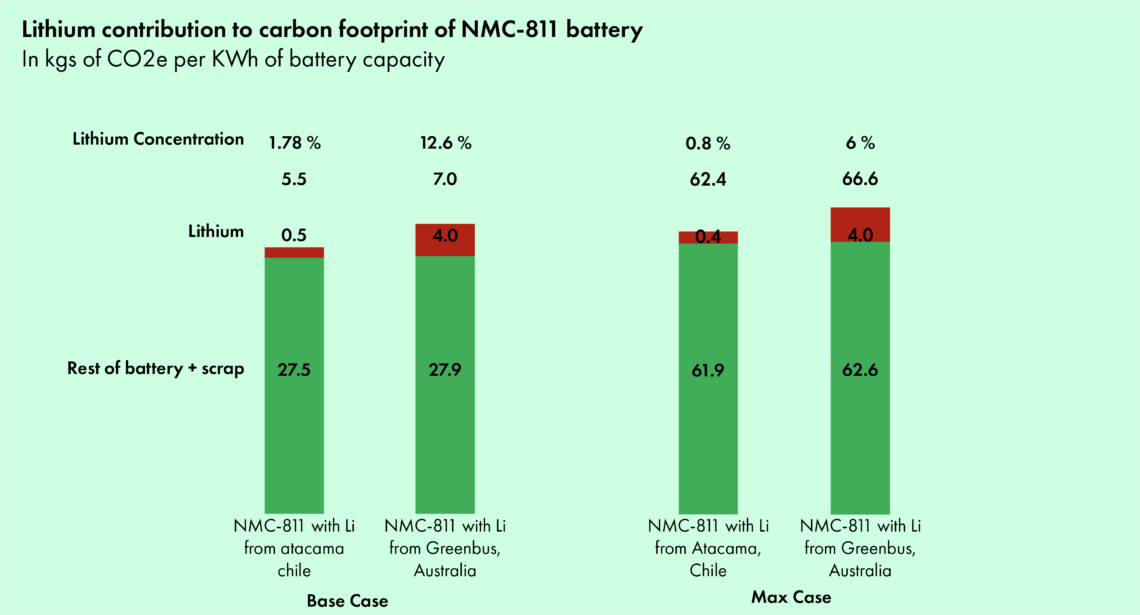

One key factor that creates discrepancies in Lithium mining, is not related to any of the on-field activities. This is the difference in models used to calculate LCA’s (Life cycle analysis a cumulation of the total emissions of a material over its lifetime).

These differences contribute to the total GHG emissions of EV batteries. Take an illustrated example of an NMC 811 battery

Lithium sourcing will become a critical aspect of focus for battery makers. Further, OEMs will have to start focusing on the method of sourcing of their battery suppliers to ensure that their vehicles have lower carbon footprint. Lithium, if sourced correctly, could be the least carbon intensive material in cathode production. Companies without a strong focus on Lithium sourcing might end up making it the most carbonintensive material in their battery

With the EU battery regulation taking effect in 2025, sourcing strategies will become crucial for battery makers and OEMs. Understanding the origin of raw materials will help set initial expectations for publicly disclosed carbon footprints. As future mines are likely to have lower-grade reserves, this aspect gains even more importance. Early adoption of low-carbon sourcing strategies will allow companies to achieve better ‘Battery Performance Classes’ and comply with the EU’s maximum thresholds.

Sources:

- The US Geological Survey 2023

- Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy 2024

- IEA – Scenarios

- Calculated with a linear growth towards demand across 3 IEA scenarios – demand data per scenario – IEA Key mineral supply demand

- Jorge A Llamas-Orozco et al, 2023 – Supplementary notes

- Shayan Khakmardan et al, 2023

- Article showing Bernstein report

- Figure 8 takes carbon footprint data from Vanessa Schenker et al. 2022 (for Salar de Olaroz & Salar de Cauchari-Olaroz) but Shayan Khakmardan et al, 2023 for Salar de Atacama to ensure consistency across the article

- McKinsey Lithium Article

- Jarod C. Kelly et al, 2021

- Data from inhouse expert

- IEA – Global Lithium Demand

- Adamas intelligence

- Vanessa Schenker et al. 2022