The European Union’s “Battery Passport” initiative (New Batteries Regulation1) aims to enhance battery production and usage sustainability throughout the EU. This initiative focuses on improving the traceability of battery materials and encouraging the recycling of components like nickel and cobalt. By 2027, all electric vehicles (EV) and industrial batteries on the EU market will require a unique battery passport to be identified with a QR code, providing detailed information on the sourcing and lifecycle of their materials, thereby promoting circular economy practices. Nickel production stands among the most GHG-emitting parts of a battery’s output, representing, on average, a third of total GHG emissions2 for high-nickel batteries. Indonesia’s role as the most significant producing and refining country worldwide, with a highly polluting production process, will be central to battery decarbonization. Thus, balancing sustainable new production with robust recycling strategies, including initiatives like the Battery Passport, will be crucial in navigating the complexities of the evolving nickel market and supporting the clean energy transition.

Nickel is advancing battery performance and causing its carbon emissions to soar

The exponential growth in EV production worldwide is reshaping the global economy, especially regarding raw material requirements. Central to this shift is the skyrocketing demand for nickel, a critical component in EV batteries. In 2023, global EV sales neared 14 million units, 18% of all cars sold marking a 35% increase over the previous year, and this trend shows no signs of slowing down. Depending on the scenarii, The International Energy Agency predicts that by 2030, EV sales will account for between 40 to above 60% of all new car sales globally3. This surge directly correlates with a burgeoning need for nickel in battery production due to its role in energy-dense batteries that power these vehicles.

Nickel is indeed a cornerstone in modern EV batteries, particularly in the development of high-energy-density battery chemistries. Among the two leading types of batteries in the EV market, lithium iron phosphate (LFP, 40% market share) and nickel manganese cobalt (NMC, 57% market share) batteries4, the latter dominates due to its superior energy density and storage capacity. NMC batteries are favored in Europe and North America, where long-range EVs are in higher demand. The evolution of NMC batteries, from NMC 111 (which contains equal parts nickel, manganese, and cobalt) to NMC 811 (with eight parts nickel to one part manganese and cobalt each), highlights the growing importance of nickel. This shift is driven by the need to reduce reliance on expensive cobalt while enhancing energy storage capabilities.

The use of nickel in batteries significantly improves energy density, making it a crucial component for extending EV range, lowering costs per kilowatt-hour, and improving overall battery performance5. Nickel-rich batteries have an energy density of approximately 150 to 220 Wh/kg, which is nearly double that of LFP batteries with an energy density of 90 to 120Wh/kg6.

For battery production, only high-purity nickel is suitable. This quality of nickel is derived primarily from two types of ore: sulfide and laterite. Sulfide ores, while easier to process, are relatively rare and decreasing in availability. In contrast, laterite ores are more abundant, particularly in regions like Indonesia, but require an energy-intensive and environmentally challenging extraction process known as High-Pressure Acid Leaching (HPAL). Nickel Pig Iron (NPI) can be converted to nickel matte to produce high-purity nickel, though its use remains limited, as NPI is generally a swing product between stainless steel and battery applications. As a result, the main feedstock for high-purity nickel production is gradually shifting from sulfide ores to laterite ores.

However, as the industry moves towards reducing the environmental impact of lithium-ion batteries, the focus often lands on nickel due to its significant contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. For example, in a NMC811 battery, which uses a high proportion of nickel, the total GHG emissions associated with its production are estimated at approximately 77 kg CO2eq8 per kWh of storage capacity. This figure includes emissions from mining, material processing, and manufacturing stages. Crucially, of this total, 25 kg CO2eq per kWh—about one-third—comes directly from the production of nickel sulfate. This makes nickel production a significant leverage point for reducing overall battery-related emissions.

A central role for Indonesia, which will continue to grow, despite a production process twice as dirty as the industry average

As of 2022, global nickel demand reached 3 million metric tons, with over 60% of consumption directed toward stainless steel production9, while battery demand represented around 16% of total nickel consumption. However, the rapid growth of the EV sector has led to an unprecedented increase in demand for battery-grade nickel: the battery segment has grown from 4% in 2010 to over 15% in recent years.

Nickel production is concentrated in a few key regions, with Indonesia and China leading the charge. Indonesia, which holds the largest reserves of laterite nickel ore, has seen a massive influx of investment in recent years as part of its national strategy to become a global hub for nickel production. In 2022 alone, Indonesia produced 1.6 million metric tons of nickel, accounting for more than 49% of global output10. The refining is, for now, more diverse, with Indonesia representing 38,4% of the world share, China 27,4% and Russia 4,7%11. However, the environmental costs are significant. Indonesia’s nickel refining processes are among the most carbon-intensive in the world. The country relies heavily on coal-powered electricity, which significantly increases the carbon footprint of nickel production. A comparison of six nickel sulphate production routes reveals that emissions levels at the best-performing facilities, located in Canada and Finland, are 70% and 63% lower, respectively, than the industry average of 18 kg CO₂ per kg of nickel in nickel sulphate12. In contrast, the high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL) route, increasingly popular in Indonesia, produces almost twice as much emissions as the industry average, with 36.8 kg CO2-eq per kg of nickel. And processing laterite ores into nickel pig iron (NPI), then converting it to matte and finally to nickel sulfate, produces emissions five times higher than the industry average.13. This presents a major environmental challenge as demand for nickel continues to rise.

Indonesia’s role in nickel production is expected to continue expanding significantly by 2030, driven by its large laterite ore reserves and increased refining capacity. Indonesia is set to account for around 60% of global nickel mining and 45% of nickel refining capacity by 203014. Since re-imposing a ban on raw nickel exports in 2020, the country has focused on building a domestic refining industry, attracting billions of dollars in investment from Chinese and Western companies15. The high environmental impact of laterite nickel extraction has prompted calls for stricter environmental regulations and the development of cleaner technologies. Indonesia currently also has the highest mining-related deforestation rate worldwide16: Nickel mining in Indonesia has caused up to 153,364 hectares of deforestation have occurred within the boundaries of Indonesia’s nickel concessions since 2000. In Sulawesi, 36% of forested land is occupied by nickel concessions, threatening biodiversity and reducing the forest’s carbon sink capacity.17

Moreover, coal-fired generation still accounts for about 60% of the power generation share18. The country plans to increase coal power capacity: by the end of 2022, Indonesia had 18.8 gigawatts of coal power under construction. Notably, 69% (13 GW) of these new coal plants will be “captive,” dedicated to powering industrial and commercial consumers rather than the grid19. This includes facilities for aluminum smelting and nickel and cobalt processing. This reliance on GHG-intensive production methods remains a significant obstacle to meeting global climate goals.

The path forward: meeting the growing demand for nickel through recycling, the development of new processes, and the use of renewable energies

The future development of nickel is driven by a projected increase in demand, with estimates indicating that global nickel demand could surge to 4.2 million metric tons by 203020, largely fueled by the EV sector if NMC batteries stay the leading type, but also by growing stainless steel absolute demand. This demand necessitates significant expansions in production capacity. However, reliance on Indonesia introduces geopolitical risks related to supply stability amid potential regulatory changes, the fight against corruption, and environmental concerns21.

To mitigate these risks, industry stakeholders must prioritize recycling efforts. The recycling process for lithium-ion batteries involves three main steps22: pre-treatment, metal extraction, and product separation. In pre-treatment, the battery casing is removed, and cathode materials are separated. Two main industrial methods are used here: pyrometallurgy, which can handle various chemistries in one process, and the more contamination-sensitive mechanical treatment, requiring disassembly and sorting. Manual or semi-automated processes are common due to high automation costs. Metal extraction typically relies on pyrometallurgy, hydrometallurgy, or biomineralization, with hydrometallurgy being the preferred method to recover metals like lithium and cobalt through acid solutions and reducing agents. Finally, product separation is achieved via selective precipitation, solvent extraction, or electrodialysis. While hydrometallurgy requires lower energy input than pyrometallurgy and does not produce hazardous gases, but it generates hazardous waste, signaling room for improvement in LIB recycling. As a result, combined Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions are significantly higher for a Mech-Pyrolisis-Hydro route (0,8 kg CO2e/ kg module equivalent) than a Mech-Hydro process (0,3 kg CO2e/ kg module equivalent), but the gap gets thinner when also accounting scope 3 (respectively 2,6 and 2,3 kg CO2e/ kg module equivalent).23

Some studies indicate that recycling from spent lithium-ion batteries can recover 95% of the metals24, significantly reducing the need for new mining. Improved recycling technologies could ensure that the annual recycling nickel could cover between 67.7 % and 96.6 % of the demand for EV batteries in China in 2050, depending on the scenarii.25 It is more than needed, given the fact that, with the EU’s “Battery Passport”, Batteries must contain a minimum of 16% cobalt, 85% lead, 6% lithium, and 6% nickel from non-virgin sources by 2031. But batteries are long-lasting products, and recycling is not the main answer for the next ten years of supply.

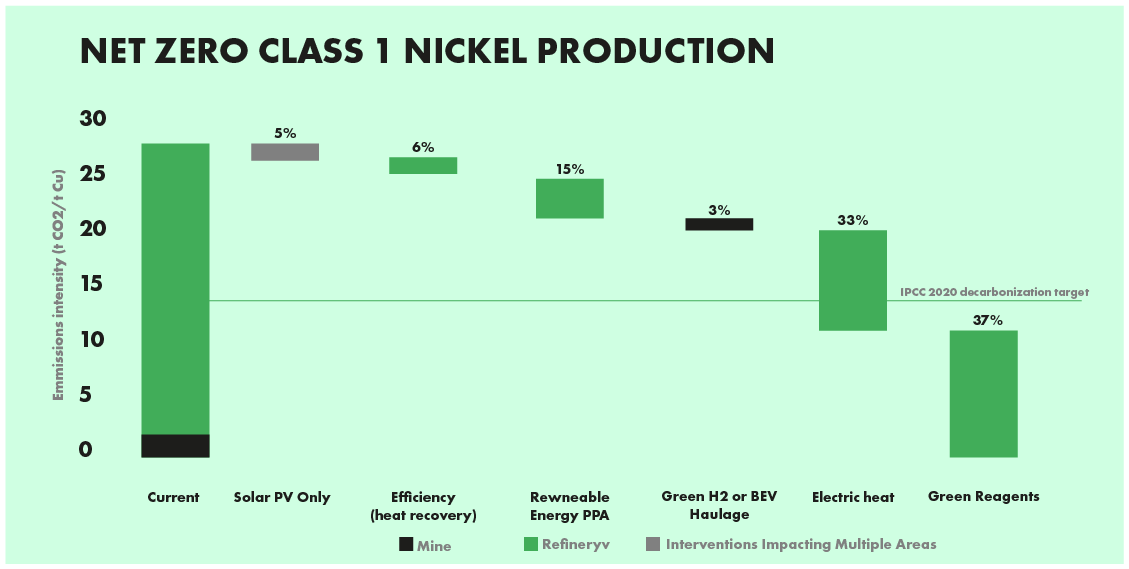

Among various decarbonization strategies, switching to renewable or low-carbon energy sources can reduce emissions by up to 40% on average in nickel production26. Other critical strategies for mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions include using zero-carbon chemicals during processing, electric heating, decarbonizing mining vehicles, and optimizing logistics. For the specific Class 1 Nickel Production from HPAL, the IFC modelizes the options in the following manner27:

Additionally, adopting more energy-efficient ore processing techniques is essential. For sulfide ores, bioheap leaching and pressure oxidation can lower energy requirements, while for laterite ores, heap leaching and atmospheric hydrometallurgical processing are key solutions for reducing the industry’s overall carbon footprint. For instance, deep-sea mining nickel production via nodule collection by TMC Mining is meant to surpass not only Indonesian nickel but also all other major land-based production methods, achieving an average emissions reduction of 70-80%.28 Indirect effects and risks of deep-sea mining, however, should be considered, such as ocean destabilization, species extinction, habitat destruction, and impacts on global food security.29

From mines to miles: how Nickel is driving the EV revolution

In conclusion, the journey toward decarbonizing batteries and achieving sustainability in the electric vehicle (EV) sector is complex and fraught with challenges. Nickel plays a pivotal role in this transition, being essential for high-performance batteries, yet its production is currently linked to significant greenhouse gas emissions and environmental degradation, particularly in Indonesia. The EU’s Passport Battery initiative aims to address these concerns by enhancing material traceability and promoting recycling, setting a standard for responsible sourcing. However, as demand for nickel is expected to carry on rising, a multifaceted approach is required—balancing the need for new production with robust recycling strategies and the adoption of cleaner technologies. While advancements such as renewable energy integration and innovative ore processing techniques offer promising pathways for reducing emissions, the road ahead is long. Achieving a truly sustainable battery supply chain will necessitate collaboration across industries, regulatory frameworks, and technological innovations to ensure that the benefits of the EV revolution do not come at the expense of our environment. The commitment to decarbonization must be unwavering as we navigate this essential transition towards a cleaner future.

Find other articles on this page.

2 PNAS Nexus, “Estimating the environmental impacts of global lithium-ion battery supply chain: A temporal, geographical, and technological perspective”, 2023

3 IEA, Global EV Outlook 2024, 2024

4 ibid

5 Nickel Institute, “How nickel makes electric vehicle batteries better” 2023

6 Mayfield Energy, 2023

7 Roskill for the European Commission, “Study on future demand and supply security of nickel for electric vehicle batteries”, 2021

8 PNAS Nexus, “Estimating the environmental impacts of global lithium-ion battery supply chain: A temporal, geographical, and technological perspective”, 2023

9 BGR, “The importance of Indonesia for the global nickel market”, 2024

10 IEA, Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024

11 BGR, “The importance of Indonesia for the global nickel market”, 2024

12 Transport & Environment, Paving the way to cleaner nickel, 2023

14 IEA, Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024

15 Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2021

16 WWF, Extracted Forests, 2024

17 Mighty Earth, “Sourcing responsible nickel for Evs” 2023

18 IESR, Indonesia Energy Transition Outlook 2023, 2023

19 GEM, 2023

20 IEA, Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024

21 Trytten, Lyle, Will Cheap Asian HPAL Save the EV Industry from its Looming Success? 2020

22 Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2022

23 Umicore’s Calculations

24 Redwood Materials, 2023

26 Transport & Environment, Paving the way to cleaner nickel, 2023

27 IFC, “NET ZERO ROADMAP TO 2050 For Copper & Nickel Mining Value Chains”, 2022

28 Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, LCA, 2022

29 African Mining Review, 2024